Most apartment tenants dream of lower rent payments and detest increases. The same is true of those who live in mobile homes. One big difference; apartment dwellers can more easily move while mobile home buyers own their home. That makes comparison difficult, so what determines “fair” park rent?

Abundant tools exist to make economic comparisons by market area. Ultimately, the question is and should be, based on consumer preference, supply and demand. A quick look at history:

Our industry’s biggest problem was running out of park spaces. Back in the 1960s and early 1970s when the mobile home industry boomed—producing homes at many times current rates—new park spaces were being created at 100,000 to 200,000 spaces per year. Two-thirds of mobile home production went to parks; most of them new. Those were the glory years when mobile home production caught up with new single-family starts and industry millionaires were rife. Nearly half the parks surveyed for Bernhardt’s Building Tomorrow had no vacancies and more than 40 percent had waiting lists. Industry associations and all participants focused enormous efforts on developing more parks. Ever-increasing numbers of mobile homes were being placed on private lots.

My, how things have changed. Now there are few existing parks, negligible new ones and parks absorb just a third of much-reduced production. Parks are being closed faster than new ones built, the industry is in tatters, and a surprising number of remaining parks have vacancies. What’s going on?

This is more than an industry problem. Our nation decries the lack of affordable housing on one hand and turns handsprings to block housing development on the other. Political “solutions” try to subsidize “decent” homes for all, with astonishingly poor results.

A NIMBY prayer:

The cheaper the home, the further from me.

It’s actually trashy people the neighbors don’t want.

Single-wide mobile homes are HUD-approved housing; everywhere. When sold to residents of well managed mobile home parks, they create compact single-family communities at cost to the resident lower than, and appreciated more by residents and neighbors, than low-rise apartments. Nobody has more incentive to maintain a viable community than the owner of the land. Nobody has more incentive to maintain the value of their home than its owner. Everybody wins.

So why not just build nice new mobile home parks? Well, land is expensive and its use controlled by elected governments answerable to the populace. They might allow a new park, if filled with upscale double-wides having garages and all the bells and whistles. They’re fine parks but do little for the nation’s need for efficient low cost housing. Years and compromises are required to obtain approvals. The resulting larger lots and higher-priced “manufactured homes” wind up hard to distinguish from nearby conventional low-end subdivisions. More existing parks close than open, and our industry loses the competitive edge they held when mobile homes cost more per square foot than stick houses.

Far too many remaining parks are fully amortized and owned by retired families who do their own fixin’ and find it easier to avoid increasing rent than provide proper maintenance. Most are “Mom & Pop” parks filled with long-term low-income residents who eventually go to nursing homes or die. Their poorly maintained “trailer” is sold or rented to lower-income-unscreened residents—the “trailer trash” so frequently featured in the media. While no one notices, nice parks become slums. Much the same happens to many mobile homes on country lots.

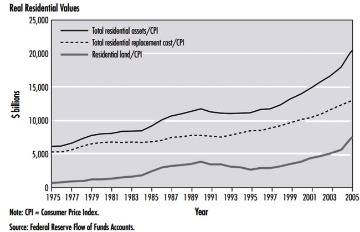

Back in the Seventies, land cost as a proportion of a conventional house cost was about 20 percent of its selling price. As the chart above shows, by 2005, it was more like half (the dotted line shows calculated replacement cost—the top line reflects the increased value of remodeled homes new construction). Land and construction cost have both grown faster than inflation. Single-wide mobile homes have not, while getting bigger and better.

In 1974, typical park rent was about $60 per month. Inflation alone suggests current space rent should be $360 a month, and in well-managed parks, it is. Too many are half that. Well-maintained buildings, including mobile homes in decent parks, now hold their value with or exceeding inflation.

Arthur Bernhardt’s biggest concern for the future was that in tough times (which were in clear sight as he finished his massive study), the industry would fragment further, each component defending its own portion of a declining market. And that’s exactly what happened. Every man, woman, journalist, association and segment of this complex industry blamed each other for the catastrophe. The Park Concept; the industry’s greatest innovation that powered the golden Sixties, is a shadow of itself, but still accounting for a third of mobile home sales. That’s the back story on the “Mobile Home Stigma”.

We lost the park developers. They gave up on park construction and switched their attention to more traditional projects. Manufacturers chased the single-family market. Park investors were scared off by the stigma. Most parks wound up in the hands of small-time owners living on cash flow of their amortized parks.

The immediate business opportunity is to buy those remaining mobile home parks having good bones for little more than their land value. Put meat on their bones to return them to their potential as communities.

Bernhardt found Seventies park construction costs (aside from land) varied enormously, but was typically $7,000 per space ($34,000 in today’s dollars). Such parks, if well managed, might sell today for something like $200,000 per space.

That suggests two possibilities. First, if one can find a skilled park developer, get a suitable piece of land at a favorable price and get it approved for a mobile home park, it might be viable to build a new one. Those are some very iffy ifs, because of the Stigma. They essentially preclude new parks in this era.

A second, far more viable plan, is for knowledgeable investors to buy good mobile home parks suffering from years of poor management. Then apply good management—fix the problems. Enforce good rules, evict problem tenants, fill vacant spaces and gradually raise rents to market rates based on the local market value of the product. A challenge, but investors large and small find it doable and profitable.

Trashy parks with unfixable infrastructure are being bulldozed for better land uses, and good riddance. If we fix the sound parks and return their rent to fair market rates over time, we’ll gradually outlive the stigma created by poor management. Once that’s accomplished, park rent can and should be further increased to enhance this increasingly desirable form of living and reflect the soaring value of the land component. Park construction can still offer relatively low cost land development in the hands of competent developers. Single-wide mobile homes offer the most affordable way to build homes of sizes suitable for today’s families. Finance and manage the land asset for its long-term value as in the Sixties, and the structures for their appraisable life span. It’s a manageable and competitive process for re-building the industry’s success formula of the Soaring Sixties.