Once upon a time, a mobile home dealer named Jim Clayton, frustrated by look-alike mobile homes, decided he could do better and opened a little factory to produce innovative mobile homes. Or tried to, before learning how difficult that task would prove to be. Clayton became very successful, but his homes look just like the competition. Innovation is hard.

I’ve never met Jim or his son Kevin, but as a wet-behind-the-ears industrial design graduate, I also set out to make mobile homes more attractive. How hard can it be? I found work with a leading mobile home manufacturer (Richardson Homes) whose new owner shared my inclination. The sketch at right helped me land my job.

After five years of trying, I spent another five on modular homes, thinking design constraints would be less. Not so. I spent another five helping build Canada’s largest mobile home producer. Innovation is hard.

Many mobile home manufacturers set out to produce innovative products, including companies owned by architects. Even Frank Lloyd Wright’s team took a whack at it. Mobile homes have improved immensely over the years, but innovative designs fail. Why?

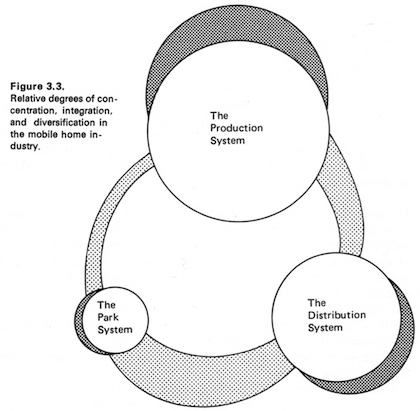

Factory construction has inherent advantages over any other method of building homes, but the factory itself is just one component. In the Seventies, MIT’s Arthur Bernhardt (Building Tomorrow, 1980, 510 pages) led a ten year analysis of the industry identifying the key components that work together—must work together for lasting success. They are:

- The Production System

- The Distribution System

- The Park System

No single part of our innovative system can stand alone, but manufacturers dominate. At that time, the five biggest manufacturers combined shared just a third of the market. They catered to their “customers”—the dealers. Half of all the homes built wound up in parks. Earlier it was two thirds; currently, just one third. Parks are the crucial but smallest link.

Jim Clayton soon learned, as did I, real innovation must consider the whole system. He integrated production, dealer and parks and came to dominate the industry. At Richardson, we spent more than we could afford on market research, design and engineering but more yet catering to dealers. Richardson attained five percent share and is gone.

No clever design; no person; no single company can initiate system change. The industry should work together. Clayton integrated the systems and prospered. Yet by the time Jim Clayton attained real success, his company was captured within the system’s limited flexibility. The easiest course is to maximize the bottom line and if the industry fails, diversify.

Even so, the system still evolves—at a snail’s pace—despite diminishing market demand. Real innovation in our disjointed industry requires the kind of leadership that enabled giants like Henry Ford or Alfred Sloan created and dominate the automotive industry. Attaining such leadership was very difficult when Bernhardt’s study was done. Easier now.

Today, Clayton produces about half of all new mobile homes, and other divisions of Berkshire Hathaway (BH) hold major shares of the finance and supply subsystems. Each is profitable and can call upon bottomless resources. BH can afford to take the long view and one might think they can’t afford not too. Yet if our industry fails—including Clayton—BH will soldier on without missing a beat. Clayton can hide behind castle walls, harassed by smaller competitors hurling invective. Clayton’s enviable success is more criticized than emulated by its competitors. Industry media (such as it is) piles on. All pursue self-interest and the downward spiral continues. Bernhardt concluded his massive analysis by noting the industry succeeded in its first fifty years by creating “… an entire new national industrial structure uniquely tailored to its specific needs”. He cautioned however, that the structure had “… not been specifically plotted”.

“What is important,” he went on, “is that its approach has been the right one. Instead of concentrating solely on technology … the mobile home industry has given equal weight to all phases of the production and delivery process.” OK, even he agreed “equal” was an overstatement, but no one succeeded in defying the industry’s evolving conventional wisdom. Too much influence was exerted by manufacturers; too little on parks. The independent middleman—the dealer—drove the process toward the lowest common denominator; price. Ever cheaper pricing drove out innovation potential. Mea culpa. We in manufacturing ignored the most critical component of the system—the customer, who chooses her lifestyle and has other options. She thumbed her nose at mobile homes, and so did the city fathers. The stigma, born in the Fifties, matured in the Sixties and crushed the industry in the Seventies.

The Mobile Home Manufacturers Association (MHMA) fought city hall, promoting upscale mobile home parks. Manufacturers supported dealers chasing volume with downscale flashy designs. A few suppliers and publications surveyed customers’ wants and needs but drew little attention. Leading industry designers formed the Design Council of Industrialized Housing, but never gained a significant voice.

In Building Tomorrow, Bernhardt devoted a hundred pages to more innovative prospects for mobile homes, but noted the industry was in “a precarious position” with no one “to shake the industry out of its present torpor”. He feared for the future of what he’d defined as the nation’s most efficient system for resolving its housing challenges. Production was already in serious decline at publication date. He described a possible “Failure Model” where production would continue system domination without building enough parks for its homes. He warned, “By the year 2000, the mobile home industry will either be alive and thriving or it will be dead.” By 2000, production was at about 40 percent of its early Seventies peak. Now it’s less than 20 percent. Only Clayton has sustained vigorous growth. The rest of the industry is taking laps in the tank.

That’s where we stand today. Never mind printed homes and whizzy architectural dreams. The only proven industrialized housing system in this country is broken and cries out for courageous leadership.